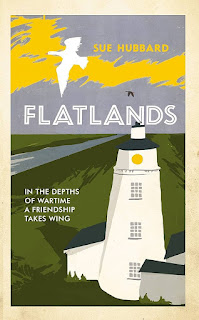

Flatlands by Sue Hubbard retells Gallico’s The Snow Goose but to an adult audience. Two souls that don’t belong, Freda and Philip, are bonded by the welfare of an injured bird: wounds and the wounded feature heavily in this wartime story. We are still evacuated with Freda but the desolation of the Snow Goose’s stretching mudflats are shifted up the coast to a “place between somewhere and nowhere” on the shores of the Wash. Hubbard’s skilled scene setting places us in both the wilderness and the time perfectly.

On “a hot day, the sort of day for a picnic, not a war” we’re transported with Freda on a train full of sad, scared evacuees to a new home “far away from love.” We’re immersed immediately in the “melancholy of the place.” This landscape, we learn as the story unfolds, matches the aching loneliness felt by both Freda and Philip. Freda remembers paisley eiderdowns and parma violets – Hubbard treats all our senses as she juxtaposes home comforts against the relentlessly barren East coast landscape.

Throughout the book the feeling of threat and uncertainty that war brings looms large but the actual menace is revealed to be lurking within the farmhouse. It is in the very place that Freda is put for safety that the full horrors of war are first exposed. She finds sanctuary at Philip’s lighthouse and they form what Philip describes as “a strange little friendship.”

An elderly Freda is telling us the story as a documentary about Dunkirk is about to be shown at her care home. Those nursed on the The Snow Goose will know Dunkirk’s poignant part in the story. I’m paddling carefully here not to avoid mines, but spoilers. During the depths of Dunkirk’s horrors in Flatlands oddly it was the addition of a dog in the water that made me catch my breath. His fate lingers long after the page has been turned.

As I read a book I make a note of sentences that I like. There was a point early on in this book that I thought I might never finish reading it because I was writing so many down. It’s a slow-paced read but with some delightful lines.

Lisa Williams is a creative soul from Leicester. She has a Masters in Creative Writing from Leicester University, and lately tends to write mostly short fiction. She likes the challenge of a word limit – usually one hundred words. Her work has been published in numerous anthologies. Lisa has a weekly story slot on local community radio. She helps out a bit at Friday Flash Fiction and Blink Ink Journal. Lisa also paints and makes jewellery selling online as noodleBubble.