(This review was originally published here.)

The Mandaeans of southern Iraq had a demon called Dinanukht, half man and half book, who "sits by the waters between the worlds, reading himself". This demon could be the patron saint of Bainesland, where characters interpret symbols that seem to belong to the external world, but turn out being part of the character's past.

These 12 stories span a range of symbolic visibility. In the epistolic “A matter of light” set in May 1816, a self-proclaimed rational man dismisses strange events as interesting physical phenomena, tricks of the light worthy of investigation. Even when he entertains the possibility of ghosts, he dismisses the notion because he's lived too virtuous a life to deserve being haunted. But we learn he's a plantation owner and that his treatment of slaves wasn't perfect. The dark shadows and the “light” of the title take on racial overtones.

In “Looking for the Castle” the symbolism's more overt. A women takes a detour to visit her home town. She has problems navigating her past. Has so much really changed? Maybe the unfindable castle's really the misremembered priory. But what is she really seeking? Was her childhood a place where she felt safe, or was it a confinement that still restricts her? After all, the fence her father built is still there.

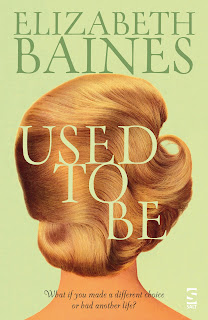

“Used To Be” includes another mindscape – two middle-aged sisters, actresses, are on their way to an amateur film-set. The journey of bridges and missed turnings becomes a metaphor ("And flashing past with the bridges are all my selves") then becomes another story to tell when they arrive late.

Further along the overtness spectrum is "Tides or How Stories Do or Don't Get Told". Fans of "show, not tell“ might balk at the 13 mentions of ”story“ or ”stories" and the discussion of narratives – e.g. "Would I mention my sense then that nothing had meaning and that my life after all was no story, or would I lie, since he recovered, and make those symbols fit a narrative arc with a happy ending?" - but to me it's like the stage magician who explains how a trick works only to surprise the audience later. What kind of story of herself does the narrator want to write?

The protagonists come in many varieties (male/female, young/old, presented in the first, second and third person), but they're all opening a debate with their past. Sometimes it's disowned - "I see her, my former self, as another person" - used as raw material to be melted down, reforged. Sometimes it illuminates the present. The settings encourage reinterpretations – film-sets, Brontë country, old haunts. Explicitly or otherwise, the characters are story-makers, reassembling their life-arc from stirred memories.

Whatever the uncertainty of the narrators, the characters are utterly believable. There's always the sensation of an underlying reality. Characters may exhibit enhanced free will once they've unshackled themselves from the past, but the real world is a given.

My favourites are “Used to be”, “Falling” and especially "Tides or How Stories Do or Don't Get Told" (which is much shorter than I recall it being). None of the stories are routine, which is no surprise given that they've all been published already in places like Carve Magazine, Unthology, Stand and Best British Short Stories. You can buy it directly from Salt.

About the reviewer

Tim Love’s publications are a poetry pamphlet Moving Parts (HappenStance, 2010) and a story collection By all means (Nine Arches Press, 2012). He lives in Cambridge, UK, teaching computing. His poetry and prose have appeared in Stand, Rialto, Oxford Poetry, Journal of Microliterature, Short Fiction, New Walk, etc. He blogs at http://litrefs.blogspot.com/.

No comments:

Post a Comment