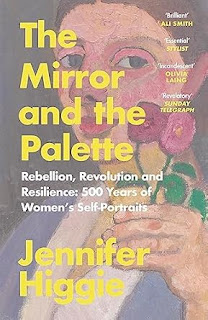

The act of self-reflection is an indulgence and one that women throughout history have seldom had the opportunity to do, more often being the object of scrutiny and worship by the male gaze. Women who flew contra to convention, female artists who rebelled against stereotype and chose introspection over objectification, have their unique stories told in this book: "A painting is a pause in life's cacophony. It does not demand conversation or justification. It does not hector her. She has stilled herself for it. It cannot and will not tell her what to do. She controls it. She concentrates, her paintbrush in hand, the mirror close by. She is defiantly, splendidly, bravely, heartbreakingly, joyously alone."

Higgie takes us on a tour of time, place, social expectations and gender battles to uncover the lives of women who dared to paint, despite objections and difficult circumstances. Reading from our present perspective, it is hard to imagine women artists being rejected from academies, refused from attending life classes or painting their own bodies, their work spurned and excluded from galleries. They often worked in secret, hoarding their work and making a record of their life for themselves only. Painting was a deeply personal act, which involved recording every stage of an aging process and for some their downfall into obscurity. Very few women made it to recognition and success. Many of these names are not known to the public and Higgie takes time to give them their due: "She looks at herself in order to study what she's made of, to understand herself anew and, from time to time, to rage against the very thing that confines and defines her."

Recent technologies have enabled wrongly-attributed works to be recognised as works by women painters. The catalogue of once-unknown artists is expanding and allowing us a better understanding of the challenges they overcame and the prejudices they faced. History is told in words and more often written by men allowing this gap in our knowledge to happen. Many of our well-known masters had patrons who bought, displayed and championed their careers. This was highly unlikely to happen if the painter was female; she was more likely to be derided for shunning marriage, motherhood and domesticity. Only two of the artists explored in this book have found recent recognition: Frida Kahlo and Artemisia Gentileschi. The rest are ours to discover.

Most of us have some knowledge of the pain and suffering that Kahlo had to overcome after a serious accident on tram as a young girl, the endless operations, miscarriages and consequent body-disfiguring impacts on her female from. These experiences are embedded into her visceral paintings, blunt self-portraits and graphic imagery. Gentileschi too had to overcome the horrific experience of repeated rape by her art tutor and endure a seven-month trial where she was tortured to prove her innocence. This manifested in her allegory paintings of religious scenes, often reinterpreted from the female perspective. To view these artworks without prior knowledge of the life experiences of the painter is to only half see them. With this book we begin to peel back the layers of each image and understand it better: "A painting will always reveal something about the life of its creator, even if it’s the last thing the artist intended. A self–portrait isn’t simply a rendering of an artist’s external appearance: it’s also an evocation of who she is and the times she lives in, how she sees herself and what she understands about the world."

In her chapter aptly named "The Liberating Looking Glass," Higgie explores the development of self-reflection. A relatively modern invention, mirrors were a luxury item; made from highly polished volcanic glass, they were like gazing into black water. Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with mirrors, both as objects and metaphors and said: "The mind of the painter should be like a mirror which always takes the colour of the thing it reflects." What such an object meant for a female artist was freedom; the ability to paint in isolation, have an ever-ready muse and to take time to become proficient: "A self-portrait is not only a description of concrete reality, it is also an expression of an inner world."

These stories are fascinating; 500 years of decadence and revolution, nobility and poverty, art movements and politics. You do not need to be an art lover or an art connoisseur to appreciate tales of women battling against the odds to create a realistic image of their own identity. In a time of the ubiquitous shared selfie, we need to understand the huge challenges these women overcame, in capturing a single expression that was often hidden from the public for decades. As Alice Neel writes, "When you're an artist, you're searching for freedom. You never find it because there ain't any freedom. But at least you search for it. In fact, art should be, could be called 'the search.'"

Tracey Foster started off in a long career as an Art and Design teacher but wanted to refocus her creative energies into writing poetry and prose. After helping others find inspiration in the world around us, she took an MA course in Creative Writing at Leicester University and has not looked back. She finds inspiration in the past and the events that shape us. Previous work has been published by Comma Press, Ayaskala, Alternateroute, Fish Barrel Review, Mausoleum Press, Bus Poetry Magazine, Wayward Literature, The Arts Council and she writes on her own blog site The Small Sublime found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment