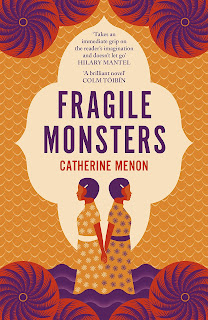

Catherine Menon is the author of Fragile Monsters, published in 2021 by Viking. Her debut short story collection, Subjunctive Moods, was published by Dahlia Publishing in 2018. She has a PhD in Pure Mathematics and an MA in Creative Writing from City University, for which she won the annual prize. She’s won or been placed in a number of competitions, including the Fish, Bridport, London Short Story, Bare Fiction, Willesden Herald, Asian Writer, Leicester Writes, Winchester Writers Festival and Short Fiction Journal awards. Her work has been published in a number of literary journals, including The Good Journal and Asian Literary Review and has been broadcast on radio.

You can read a review of Fragile Monsters on Everybody's Reviewing here. You can read more about Fragile Monsters on Creative Writing at Leicester here.

Interviewed by Jonathan Taylor

JT: What was the original starting point or inspiration for writing Fragile Monsters?

CM: The inspiration for Fragile Monsters came from the bedtime stories my father used to tell me about his own childhood in Pahang. It was only as an adult that I began to understand the context of these stories. Kuala Lipis, where he grew up, was the headquarters of the Japanese army in Pahang during the occupation.

I began to read memoirs and interviews with other people who’d lived through that time, and I was struck by the extent to which all of these speakers were taking ownership of their own narratives. They were describing what had happened to them, but with a focus on the emotional truth rather than the specific events. This was an amazing thing to realise: the sheer resilience that they had had to show in order to take back control of the past.

JT: How far and in what ways did you draw on autobiographical material in writing Fragile Monsters?

CM: Although the inspiration for Fragile Monsters came from my own family history, all the events and characters in Fragile Monsters are completely fictional. Looking more deeply, though, there are certain aspects of the character of Durga with which I feel an identity. Her desire to connect with her past and define her own interpretation of her history, her ancestors, her place in society – that’s something I can strongly relate to. So often we’re led to feel that our lives are out of our control: if we’re born into a particular society, culture or family then that will dictate who we can become. Durga struggles against that and has a fierce desire to create her own identity, even where this means moving half a world away.

More generally Durga is, I think, a representation of some of the pressures which modern women face. She’s driven to succeed and because of her chosen career feels that she has to fiercely repudiate other ways of looking at the world, such as Mary’s more slippery approach to the truth.

JT: How important is a sense of place in your writing?

CM: This is hugely important to me when writing in general, and was particularly so for Fragile Monsters. The characters are to a certain extent defined by the place: by their history, culture and surrounding society. This was a theme I kept returning to during the writing process, particularly when intertwining the history of the characters with the stories they tell each other, which are of course grounded in myth and folklore. There’s sometimes an expectation that stories from Asian cultures will be somehow made palatable to Western understanding, that the characters will be neatly placed into their boxes: the mystic, the oppressed woman, the ambitious pauper.

The thing is, of course, that stories – and even myths – don’t fall neatly into such partitionings. Durga would have grown up with a similar fusion of stories and folklore as I did: she’d have told stories of pontianaks to terrify her friends at school, she’d have waited for Father Christmas to arrive and she’d have seen stories from the Ramayana on TV on Sundays. Myths and folklore tell us something deep and true about ourselves and the place we live in. In writing Fragile Monsters it was very important to me to acknowledge the power of these stories without falling into the trap of reductionism.

JT: How important is a sense of history in your writing?

CM: Again, this was immensely important to me. I think that in general – particularly about WW2 – there’s a tendency for history books, education and popular media to focus on the war in Europe. Most people don’t even know that the Japanese invasion of Kota Bharu took place before the attack on Pearl Harbour. This is a shame, because it does a disservice to the unique stories of Malaysians living through the Occupation at the time, and subsumes their identities and narratives into a global, Eurocentric perspective.

When writing Fragile Monsters I spent a lot of time reading through old newspapers, letters and interviews in the British Library. It was very important to me to access primary sources and as far as possible to hear people tell their stories of that time in their own words.

JT: I loved how you threaded mathematical themes and metaphors throughout Fragile Monsters. What part do you think maths plays in the novel? Why do you think it arose as a part of the narrative?

CM: I wanted to explore the way we all tell stories about our past, the way we mythologise certain events and gloss over others until we’re no longer even sure what our real memories are. Obviously Mary does this by co-opting folklore and mythology to create a slippery, evasive history – but it was also important to me to show that this isn’t the only way we reinvent ourselves. Durga, of course, is the exact opposite. She values logic, certainty, a kind of rigorous and exacting thought process that doesn’t allow for something to be “right, instead of true,” as Mary tells her. But of course, that’s just as reductive a way of looking at the world, and misses out just as much.

JT: In a wider sense, do you think there are overlaps between maths and storytelling, or writing?

CM: For me, mathematics and writing come from the same creative well. They're both a search for the right way to express a concept that exists only in potentia and to communicate it to your readers. When we judge a mathematical proof we use words like elegance, interest, beauty - the exact words we use about a piece of writing. Pure mathematics consists of sitting very quietly, inventing abstract objects and thinking up relationships between them – then stretching those relationships, putting the objects together in different ways, looking at them from different angles … everything that you do with characters in a novel!

JT: How and why did you go about structuring Fragile Monsters around parallel, inter-generational stories?

CM: I knew that I wanted to tell both stories in parallel: Durga’s compressed few weeks when she’s discovering all these secrets, and Mary’s entire life which has given rise to them. There are also a number of deliberate points of confluence between the two narrative flows: the crises and tensions of Durga and Mary’s lives arise in similar ways and at similar points. I also very much wanted to show Mary as herself, rather than solely in terms of her relationship to Durga. We have so few representations of older women in literature, and a lot of those treat these women – these grandmothers, they’re often called in rather disparaging tones, as though they’re nothing else! – as essentially stereotypes.

Of course, it isn’t as simple as that. Mary’s story is in fact told not by herself but by a disembodied voice identified strongly with Durga. This allowed me to suggest to readers that Mary is, perhaps, just as much a construct and product of Durga’s imagination as she is of her own. Durga is telling Mary’s story for her, both literally and metaphorically.

JT: You write short stories as well as novels, and published a brilliant collection of short stories, Subjunctive Moods, before Fragile Monsters. How did you find moving from one form to another? What do you find are the different challenges posed by the two forms?

CM: I really enjoy both forms, but they do present such different challenges. A short story feels to me like a suspended moment, like the pause before a breath. Obviously short fiction doesn’t have to be limited in time – I’ve read some wonderful short stories, such as some of those by Jhumpa Lahiri, which cover an entire life – but there still needs to be that sense of the narrative arc being pared down to a brittle sufficiency. Novels, on the other hand, feel like an immensity of riches. They require a very strong sense of balance between the events of the plot and the development of the characters, and this needs to be sustained over 80,000-odd words. For myself, I found in moving from short stories to novels I definitely needed to recalibrate my mindset; to feel that I had room to settle into the longer work and do it justice.

JT: Are you working on anything new at the moment?

CM: I’m currently working on my second novel, which explores similar themes of science, storytelling and coming-of-age. I’m immensely excited about it, and about making friends with the new characters. It’s been hard to leave Durga and Mary behind, but I’m very much looking forward to the process of creating new characters and complexities.

Jonathan Taylor is the director of Everybody's Reviewing and the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester. His books include the novel Melissa (Salt, 2015), and the memoir Take Me Home (Granta, 2007).

No comments:

Post a Comment